The world has just witnessed “by far the largest container shipping bankruptcy in history”, writes the JOC. But the collapse of the South Korean shipping line Hanjin, the world’s seventh-largest container carrier, should not come as a surprise.

The world has just witnessed “by far the largest container shipping bankruptcy in history”, writes the JOC. But the collapse of the South Korean shipping line Hanjin, the world’s seventh-largest container carrier, should not come as a surprise.

The shipping industry is ripe for an overhaul. In the past quarter alone, 11 of the 12 shipping companies to publish results have announced heavy losses. Freight rates have been under pressure for some time, due to a combination of slow global trade and surge in capacity created by new cost-effective mega-ships.

So how can the industry find a route out of the crisis? While alliances between shipping companies have failed to reduce overcapacity, mergers might achieve this goal. Data-based systems, which improve interaction between ship and shore, offer cost reductions of up to 30%. But is it enough to significantly change market dynamics?

This chart shows the alliances created among shipping companies, and their share of worldwide capacity.

Image: Thomson Reuters

Image: Thomson Reuters

A lot is at stake: $14 billion in goods are currently marooned at sea on Hanjin ships. Container ships and bulk carriers are being denied access to ports and several vessels have been seized (or are likely to be seized) by charterers, port authorities and other parties. Around the world, Hanjin cargo ships are dropping anchor at sea to avoid losing more ships to creditors waiting on land.

South Korea’s maritime ministry expects cargo exports to be affected for another two or three months.

The collapse comes at a critical moment in the year, as retailers prepare for the holiday shopping season. The National Retail Federation in the United States fears a potential ripple effect throughout the global supply chain that could cause significant harm to both consumers and the US economy. British retailers, too, have voiced concerns about pre-Christmas supply.

Hanjin Shipping filed for bankruptcy protection on 31 August, after a long struggle to raise liquidity and restructure debt. Should shippers have seen it coming? In 2009, the container industry posted operating losses of close to $20 billion, but none of the shipping lines went under.

The shipping industry is a complex network of maritime alliances and relationships. Importers and exporters are currently finding their freight blocked on Hanjin ships – even though they booked with other lines. And Hanjin’s membership of the CKYHE alliance – which includes China COSCO, Yang Ming Marine Transport Corp and Evergreen Marine Corp Taiwan Ltd – has now been suspended. What this situation shows is that globalized trade requires new legal mechanisms to protect carriers, shippers and consumers.

What does this mean for global trade?

Short-term impact on the global supply chain will depend on the time needed to unload Hanjin ships. In the meantime, customers will have to seek alternatives while rolling out their contingency plans. Competitors will take on the additional cargo – but at a price. Hyundai Merchant Marine, for example, will deploy at least 13 of its ships to two routes once exclusively serviced by Hanjin, while the South Korean government plans to reach out to overseas carriers for help, writes Reuters.

Mid-term, the shipping industry might see healthy rates and revenues coming back. Prices have already surged upwards – by up to 50% for a 40-foot container from China to the US. The surge may be partly due to the forthcoming China National Day on 1 October, as well as the number of vessels made idle to reduce overcapacity. However, the Korea Maritime Institute has estimated that, in the near term, shipping rates will rise – by 27% between Busan and the US, and by 47% between Busan and Europe.

In light of these increasing risks and their impact on the global economy, there are two likely outcomes. First, the market and existing legal mechanisms will be left to clean up the failure. Alternatively, the South Korean government will find a way to support its struggling shipping industry.

For decades, South Korea’s shipping lines were engines of the nation’s export-driven economy. Their role going forward might depend on the assessment of their ability to significantly reduce costs and become competitive in the global market.

This blog was originally posted on the World Economic Forum Agenda.

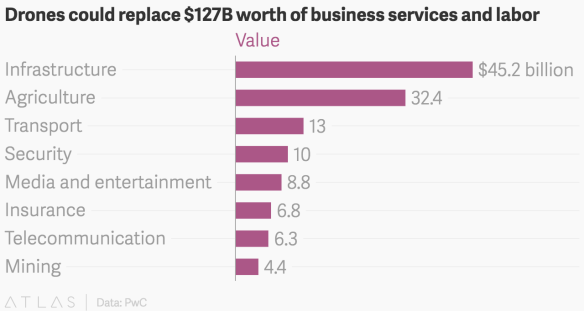

From Amazon’s delivery drones to self-driving cars, autonomous factory equipment to Elon Musk’s 760 mph vacuum tubes – automated vehicles are on the rise.

From Amazon’s delivery drones to self-driving cars, autonomous factory equipment to Elon Musk’s 760 mph vacuum tubes – automated vehicles are on the rise.